We live in one of the safest times in human history to raise kids — perhaps the safest. Yet parents are overcome with fear. Fear of crime, fear of child abductions, fear of germs, toys, and swing sets.

Lenore Skenazy writes that many of these fears are misplaced and that when we give our kids some independence, when we allow them to live the childhood that was natural to children just a few generations ago, that everyone benefits — parents, kids, and society.

She blogs at Free Range Kids.

I talked to Lenore on the phone while she was at her home in New York City.

David: One of your chapters is subtitled, “Quit Trying to Control Everything. It Doesn’t Work.” I wonder where this desire to manage and direct everything comes from? Is it just a part of being a parent, or do you think something’s changed in our society where we feel the need to govern every little thing in our children’s lives?

Lenore: I do think that something has changed in society. Of course, parents are always concerned for their children’s welfare. It’s our job to keep them alive and propagate the species and, plus, we love them. But what I think has happened recently is the idea that we that can control things. We’ve almost gotten to the point where so many things that used to be beyond our control with everything from diphtheria to crashing through the windshield have become taken care of.

We have vaccines and we have airbags and we have car seats and we have cribs with the right spacing between the bars. Everything is so safe that we figure we can keep everything terrible at bay.

That’s what I was just reading today. Someone was recalling, I think, two million baby monitors because two children in the last ten years had gotten strangled, which is horrible, in the cords. The idea was if only there were no cords or if only there were signs on the monitors in big letters — “Don’t put a cord anywhere near the crib” — that nothing bad would ever happen.

Yesterday I had a piece on my blog about somebody had put up a tire swing in his town and the town was threatening to take it down. One woman wrote and said, “They should take it down. I was on a tire swing as a kid and it hit me in the eye and I am now blind in one eye. They should all be outlawed.” That’s sort of the way we look at life now. If anything bad ever happened once to anyone in the world having to do with anything, we get rid of it.

Truthfully after a kid in New York City was killed by a falling branch in Central Park, which is an unspeakable tragedy, people were seriously chatting about well, you know, maybe these trees are too dangerous. Maybe we have to get rid of them. Maybe we have to inspect them more. The idea that anything bad could ever happen is so horrendous to us and we always look for somebody to blame and the person to blame always ends up, generally, being the parent, that parents are being driven to the point where they have to think far into the future of the consequences of any decision and try to control it right at that instant.

“I think if our parents had thought this way as we were growing up, we couldn’t have walked to school. We couldn’t have ridden our bikes to the library. We couldn’t have spent any time at the public pool without them there. We really would have had a very indoors, quiescent, un-exploring life, which is what we’re giving our kids.”

David: Just to review for people that don’t know your back story, you allowed your nine year old son to ride the subway home on his own a few years back. In hindsight, this story has several key elements that pushed it into the tabloids and morning news programs – kid’s safety, New York City, the subway, a potential crime. You almost couldn’t have dreamed up a better promotional story, could you?

Lenore: It’s amazing to me, but having been a columnist for about six or seven years at that point and having written, probably, a thousand columns, 999 of which never gotten any public attention whatsoever, never landed me on the “Today Show,” of course I was shocked by the reaction to that particular column.

David: Living in New York City, in general, it has to be a very unique upbringing for a child. Could you talk a little bit about why you chose to raise your kids in the city? Some of the pros and cons of living in New York and what are some of the kid-friendly attractions in New York that you couldn’t imagine living without?

Lenore: For me, it’s very, it’s an easier place to raise a kid than where I was growing up. I grew up in the suburbs, and my mom had to drive me to ice skating lessons. She had to drive me to Sunday school. It required a lot of ferrying around. Whereas in New York, when your kid gets a little older, say nine, they can get themselves places because there’s a lot of public transportation, and moreover there’s a lot of people around all the time, which I believe makes it very safe. I think that there’s safety in numbers. I think most people are good. So, if you have a lot of people around, you can have your kid outside and there’s a lot of people looking after them or whom they could ask for help if they needed it.

As far as fun things for the kids, I think there’s sort of normal things that they like. They like the park except it happens to be Central Park. They like apples, but it happens to be at the Apple store, like Steve Job’s Apple Store. My one son loves going there. Actually, both sons like going there and just playing with gadgets. They get themselves around. They meet friends for a movie. It’s an easier place for a kid to be self- sufficient than the suburbs after a certain age.

David: In many ways it seems reasonable to warn your kids, to warn kids and parents about everything. What’s the harm in a warning? But there are costs to this way of living, to this way of thinking. Costs for our kids, costs for the family, costs for us parents, aren’t there?

Lenore: It’s sort of a new way of looking at life. Thinking of everything in terms of not only a risk at that minute but a risk 30, 40, 50 years down the line. If I give my kid a Cheeto now, is he going to hang on to that orange dye number seven for the next 30 years and then develop a lump in his pinkie? Who knows what’s going to happen. Really, was this something I should’ve done for the kid or not? Shouldn’t I have grown my own Cheetos?

It’s a very obsessive way of thinking, and it can drive you crazy because . . . I call it “worst first.” You sort of think of the worst possible consequences of every action first which leads to some paralysis. If you think that your kid is going to be abducted in the two blocks walk to school with his friend, you won’t let him walk to school. If you think that the bus driver is possibly a molester, then you won’t let him ride the school bus. What do you end up doing? You end up having to drive them, without thinking of those risks — for some reason driving always gets a pass. You never think about the possibility of him dying in a fiery car crash or choking to death in 30 years due to the emissions that have grown untenable because everybody’s driving their kids to school.

It is a constricting way to think. I think if our parents had thought this way as we were growing up, we couldn’t have walked to school. We couldn’t have ridden our bikes to the library. We couldn’t have spent any time at the public pool without them there. We really would have had a very indoors, quiescent, un-exploring life, which is what we’re giving our kids.

I agree that you should be thinking ahead in terms of the potential dangers that really do exist. I think you really owe it to your kids to teach them very young and very diligently how to cross the street safely. I think you have to teach them how to talk to strangers but don’t go off with strangers. I think you have to teach them how to swim. I think you have to teach them about good touch, bad touch. Most people are good, but if anybody wants to touch you where your bathing suit is, you tell them no. Even if they say, “Don’t tell anybody,” you tell me and I won’t be mad at you.

Basic things like that, sort of like you teach them to stop, drop, and roll just in case there’s ever a fire, you prime them because that’s your job as a parent. But then you have to gradually see if they are looking both ways before crossing the street. If they have learned the route to school and if they feel ready and maybe if they have a friend who wants to walk with them and crime is down since when we were kids in the ’70s and ’80s. Crime is lower today than it has been since 1974. Then why not give your kids the kind of freedom that you, not only relished, but helped you develop.

When your parents believe in you and when you believe in yourself and you believe in your neighborhood and you believe you can do things, that’s giving you the kind of self-esteem and self-confidence and self-reliance that we’ve noticed are missing from our kids and we try to give back to them artificial ways through gold stars and trophies for showing up and good jobs for when they draw a scribble on a piece of paper.

What I’m trying to say is if we don’t give our children any freedom and any sense that we do believe that they can make their way in the world, they won’t. It’s not fair.

David: It’s hard for me to believe, but some people live in this bubble — I call it the TV bubble — where the world is filled with risks and crime and violence. When in reality we live at the safest time in human history to raise kids. Could you talk a bit about the drop in crime and some of the other factors that should be making parents happy and confident instead of worried and fearful?

Lenore: Yeah, that’s all I keep reading about. We are living in, as you were saying, one of the safest times in history. Crime has been on a 16 year decline. Our food and drugs, even though we’re always worried about something, some trace element of this or that seeping in, are actually more regulated than any time in human history. Cars are safer now. Fewer children are getting cancer than they were when I was growing up when in the ’50s one out of every 30 children would die before the age of 5. That’s one kid out of every kindergarten class would not end up in the kindergarten class, and now it’s far, far less. It’s a healthy and lovely time for children to be alive and for parents to revel in that, and instead we’re more afraid than ever.

The thing about crime is that when you do watch TV, something happens called the mean world syndrome. It’s not me who made up that term — it was a guy at the University of Pennsylvania. Mean world syndrome was something that he measured. He looked at how much time people spent watching TV, and then he gave people surveys of how bad they thought the world was. The people who watched more TV felt the world was more dangerous, more filled with criminals, crime, tragedy because, of course, that’s what television thrives on. If it was all documentaries about song birds, you wouldn’t tune in, but Nancy Grace will get you to tune in.

When they’ve actually done surveys of people, like Gallup does a survey every year — Is crime going up or down? I haven’t seen this year’s survey, which would’ve been for 2010. But in 2009, 73% of the people surveyed said crime was going up, and according to FBI statistics, crime went down 10%, the murder rate went down 10% that year. If you have a double-digit drop in crime and 73% of people believe that crime is going up, there’s a great disparity between reality and perception. I think that the more we watch TV, the greater that gap is.

“Your child is 40 times more likely to die in a car crash than to be killed by a stranger.”

David: I’m sure you’ve seen these on TV or in the newspaper — the 10 or 20 or 30 year anniversary of some tragic murder or abduction. It definitely grabs you, obviously. What if that were my kid? But then I catch myself, and say, “Wait a second. How many thousands of kids have been killed in a car accident over those two or three decades?”

Lenore: Well, I have statistics for this — not that anybody cares. People go through these paroxysms of self-doubt when they let their child walk to the park or play out on the lawn even because they can all picture a child who was on a milk carton or on one of these specials like you are talking about who did disappear and it’s an unspeakable tragedy. But they don’t think about the same unspeakable tragedy, which is death, when they put a child in their car seat and drive to the dentist’s office, even though your child is 40 times more likely to die in a car crash than to be killed by a stranger. For some reason, cars get a pass because we think we’re in control.

You will never be faulted for driving your child to the dentist office and ending up in a fiery crash because you were there. You weren’t trying to do anything wrong. But if your child dies another way with you not there, you will have fingers pointed at your from Larry King on down to Anderson Cooper down to the local paper and the PTA. Why wasn’t she there? I would never let my child out of my sight. Why did you have him if you didn’t want to care for him? It serves you right.

David: You have a chapter on childhood experts. It would be one thing if these experts gave us good advice. If we read a book on safeguarding our home and our kids were instantly safer. But much of the common safety advice makes no difference at all, does it?

Lenore: Well, it depends. My chapter on experts is not just about safety, like how to secure your child in the house or how to keep them safe from kidnapping. A lot of it had to do with that fact that there are people telling us how to live every single aspect of our life with our children down to what to eat when we’re pregnant, what mobiles to hang over the crib when they’re born, how to have a conversation about a picture the child drew.

I read a chapter in one of the how-to books about how to discuss that really, really difficult subject. How to have the conversation about the tooth fairy, as if these are things that no parent could possibly navigate on their own or figure out that maybe they should eat some vegetables while they’re pregnant. Maybe they should sing a little bit to their kid when the baby’s born. Maybe they should not feed them beef jerky as their first meal. There’s stuff that is pretty common sensical to parents and nobody gives credence to.

You have to have been taught exactly how to do it precisely right by some expert. Then if you don’t, if there’s that one meal you trip up . . . like this morning, my kid was so un-hungry and I didn’t want him to go school without eating anything. I tempted him with toast. I tried to get him to look at the cereal cabinet. How about an egg? No, no. Okay, I had a Kit Kat in my purse. How about a Kit Kat? “Oh, I’ll eat a Kit Kat.” You know what? I was happy he ate a Kit Kat instead of going to school hungry and later realizing he was hungry.

If I had read a book, I’m sure it would’ve told me never have any candy before 8:00 in the morning. Don’t set a dangerous precedent feeding your child candy. Don’t you realize that most cavities occur if the child won’t be brushing his teeth until late that night. There’s absolutely no nutritional value to candy. This will only cause him to have a headache later and do poorly on his SATs. I mean there’s like so many things that every decision could be determined by according to the experts, but, frankly, seat of the pants works for me. Works for most kids. Our species has made it to this point, 300,000 years of human evolution before there was a section in Barnes and Noble called parenting.

David: You’ve, obviously, done a lot of thinking on child safety tips – the good ones, the bad ones. What safety precautions stand out for you as being really useful, as actually making a difference and keeping kids safe?

Lenore: The ones I was talking about before. Teach them how to cross the street. When I spoke to the head of the Crimes Against Children Research Center, David Finkelhor, about all these exhortations. Don’t write your child’s name on the backpack. Somebody’s going to see it through a telescope and then come up and say, “Hi, Barry. I’m your mother’s friend, Barry.” It turns out that that’s a stupid piece of advice. It never happens. Besides of which if they wanted to figure out that you were Barry, they would just stand near you and listen to your friends talking to you for a few minutes.

To keep your children safe from child molesting, really, which 90% occurs at the hands of somebody they know not a stranger, so don’t emphasis stranger danger, emphasize the idea that you can teach good touch/bad touch to children as young as age three. Bad touch is anything that has to do with anybody touching anywhere that’s normally covered by a bathing suit. That you can tell you parents that somebody . . . first of all, you can say no to an adult.

Secondly, even if an adult says, “Don’t say anything about this. This is our secret,” you don’t have to have a secret. Come tell me. I won’t be mad at you. That turns out to be far more protective than placing thousands of more people on the sex offender list or getting the sex offender app and looking for houses near you. The sex offender list is just riddled with people who pose no threat to children as well as a few who do, but you can’t distinguish them on a map.

David: You sort of stumbled into this role — Do you think you’re making a difference?

Lenore: I’m positive I’m making a difference because every day I get letters from people saying, “I was worried about letting my kids who are six and seven play on our front lawn, but then I read your book and I decided what am I worried about, they’re together. I’m right inside. They know to call. They know . . .” “Why did I get a house with a lawn if not to have the kids play on the lawn?” So I know that individually people are changing. It’s hard to change a whole society, and that’s the real challenge. Individuals will be able to absorb this message. But the society is still bucking the idea of children being safe or competent because there’s a lot more money to be made making us fearful.

First of all, you can show a “Law and Order” show about a kid being abducted or kidnapped or raped or murdered, and that’s going to be a show that grabs a lot of viewers. So they’re not going to change. Then the news is always about what’s the most scary — what’s the most horrifying. Stay tuned, the killer in your kitchen cabinet tonight at 9:00! That’s not going to change.

The toy stores and baby supply stores are filled with objects that supposedly provide safety for our children, but what they really do is provide us with a new fear of a very far fetched, unlikely danger that they then assuage with the product. So they’re not going to be in the business . . . the people who sell baby knee pads are not going to say, “Boy were we crazy. This was a silly thing. Obviously, children have been crawling since the beginning of time. They have soft knee pads at that point. They have got a soft big bottom not to mention a diaper. They’re going to fine without these things. Forget it. We’re taking them off the market.” So the marketplace is working. There are all the parenting magazines that have to put something scary on the cover. Is your child at risk for AIDs? How safe is your nanny? Is your child in the wrong school? Because if they said everything’s fine, don’t worry about it, and go about your lives as you were, nobody would buy that magazine and besides of which it couldn’t push any products.

While I feel like parents who read my book or look at the blog or just think about these things on their own and sort of take a step back and think, gee, we survived without all this stuff, those people are going to be changing and they are changing. But there’s a lot of money riding on people getting more afraid.

David: I don’t think any one issue or event quite captures the absurdity of our fear as succinctly as Halloween and the fear of poisoned candy and all the time, energy, and public warning that go into defending us against a risk that has never been shown to hurt anyone.

Lenore: Yeah. What I finally realized about Halloween is it’s our test market for parental fears. It started with the fear that our children were being poisoned by strangers’ candy. The idea behind that is, of course, the people who look normal and nice who live in our neighborhood are really all potential child killers and we should treat them as such. We should assume that anytime they give our children candy, unless it is sealed hermetically at a factory, it is taboo and possibly murderous. So that starts us thinking in a very strange way about our neighborhoods. Right? It’s not that it’s filled with neighbors, it’s filled with potential child killers. Once we started giving that any credence on Halloween, we started giving it credence on the other 364 days of the year and keeping our children inside and telling them not to say hello and walk fast past the neighbors. Never go knock on a door, and Girl Scouts aren’t allowed to sell cookies by themselves anymore. Now they have to have an adult with them. Everything became stranger danger. That was one fear that got sort of ramped up by Halloween.

The other thing is that now on Halloween in many states or different municipalities, if you are on the sex offender registry, you are not allowed to answer the door for fear that you will rape the children who come to the door. In some places, you’re not even allowed to have any lights on in the home lest that lure an unsuspecting child into your lair.

Then there was a big study done this year by three academics and I can’t remember their names. They studied 37,000 cases of sex crimes from 1996 to 2006, I think, ever since the escalation of the sex offender laws. They found absolutely no rise in sex crimes on Halloween even before these draconian laws were passed or after. In fact, the academic that I spoke to said they were thinking of calling their paper, “Halloween the Safest Day of the Year.”

Why is it safe? Because people are outside, because children are back outside, because some adults are outside, so that’s the ironic thing. We are safer the more we are outside, the more we are communing with our neighbors, the more we become a community again. Yet, all the fears, there are sex crimes out there and these guys are going to snatch you in and you shouldn’t answer the door, people are poisoning candy — which has actually never happened in the history of America as Joel Best, the academic who has studied child poisonings, found out.

The fact that we have taken all of these to heart as if they were real threats and absolutely changed the holiday as a result and taken it indoors, into the community centers, into the churches, parentally supervised, taken children off the streets, told them they’re not competent, they’re not safe, they need be hot-housed for them to be safe, that just became the template for all parenting. So I think if you look at Halloween and any of the trends that we see on that particular holiday, you’ll see exactly where childhood is going.

Further Reading:

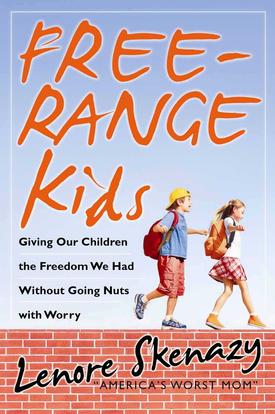

- Free-Range Kids (Amazon affiliate link)

- Free Range Kids – The Blog

- Motherlode – Great blog about parenting by KJ Dell’Antonia

- Playborhood

- Slow Family Living

About Santorini Dave